Initiatives

The restoration and preservation of the Konotori

This is the story of Konotori (also called the Oriental White Stork), which was once extinct but has now been successfully reintroduced into the wildlife of Toyooka.

Background

We are working on an unprecedented project to breed once-extinct wildlife in captivity and reintroduce it to its former habitat. What is our motivation for expending considerable time and expense to bring back an extinct bird? Human beings are responsible for driving it to extinction, so it is our duty to bring it back. In addition, this efforts aids preservation of the species. Moreover, we believe that restoring a rich natural environment for the stork to live in also enhances our own lives.

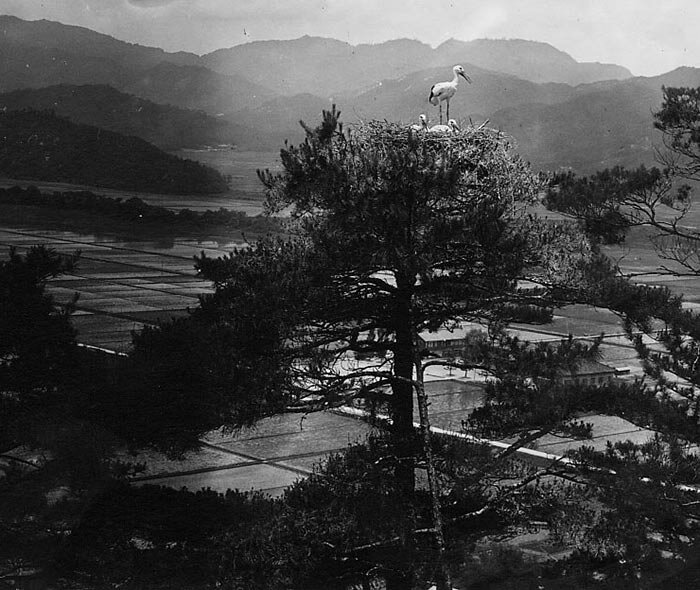

The Oriental White Stork

The Oriental White Stork is one of the largest birds in Japan. Its main feeding grounds are paddy fields and river shoals. This stork is a carnivorous bird that eats fish, frogs, snakes, grasshoppers and locusts, etc. It lives not only in Japan, but also in Russia, China, and South Korea. With only approximately 3,000 believed to be left in existence, the Oriental White Stork is considered an endangered species.

Why did the Oriental White Stork go extinct in Japan?

The Oriental White Stork once inhabited all of Japan, but in the late 1800s, they were hunted at gunpoint and their numbers decreased dramatically. Following World War II, in the 1950s, the area dedicated to paddy fields decreased as Japan underwent development during a period of rapid economic growth. In addition, farms began large-scale use of agrochemicals and pesticides. As a result, creatures such as frogs and fish in paddy fields drastically declined, and the storks lost their habitat. In 1971, the Oriental White Stork completely disappeared from Japan.

Why did Toyooka seek to protect storks?

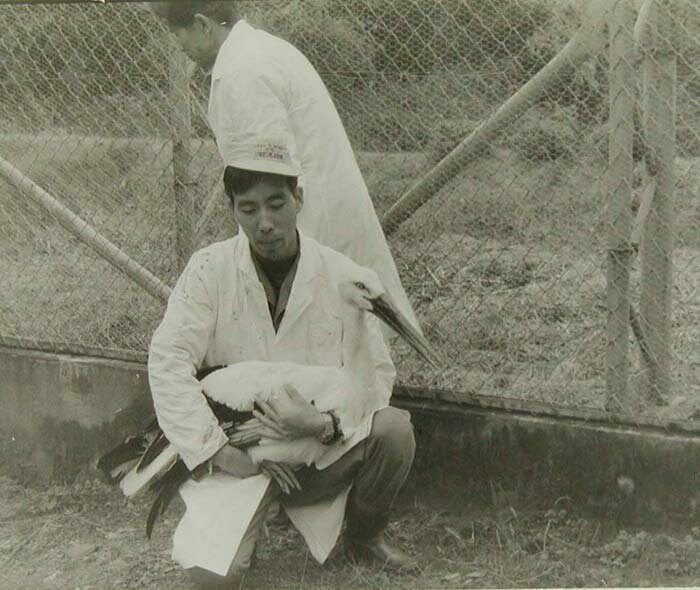

In 1965, shortly before the storks became extinct, Toyooka captured wild storks and began artificial breeding. Yet the storks’ bodies had been damaged by mercury poisoning from agrochemicals, impairing their ability to breed. The turning point was the transfer of six storks from the Khabarovsk region of Russia in 1985. This pool led to a successful pairing, and in 1989, a chick was finally born.

Bringing the storks back to the sky

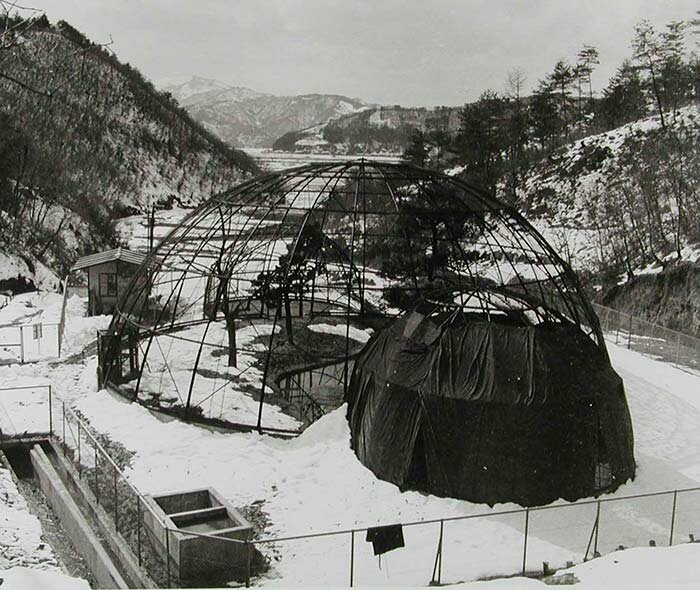

Once the storks began to consistently breed in captivity, we started initiatives to return them to nature. Hyogo Prefecture and Toyooka established key facilities for the reintroduction of the Oriental White Stork into the wild, as well as public awareness facilities about this project.

We also worked on the restoration of rice fields and rivers, which are the natural habitat of the stork. The city also undertook production of pesticide-free rice with local farmers.

The initiative further grew with the cooperation of various groups collaborating together. And then…

A miracle occurred

In September of 2005, five storks being bred in controlled conditions were released into the wild. Two and half years later, a chick was born in the wild for the first time in forty-six years.

Today, several pairs of storks keep nests in Toyooka, with chicks leaving the nest each year and numerous storks flying through the skies of Japan. Seeing the storks in the sky has become almost commonplace today.

When we began artificial breeding, who could have imagined that the storks released would come back and grace us with their majestic sight? Through the efforts of countless people continuing to strive to bring this landscape – one where storks can be seen close at hand – back, we succeeded in reintroducing them to the wild and bringing them back from the brink of extinction.

Coexisting with the storks

We remain hard at work on various initiatives to create a stork-friendly environment. These include the development of artificial wetlands to foster the growth of living creatures, environmental education towards sustainability initiatives, ecotourism, and efforts to create a positive feedback loop through the environment and economy, such as through stork-friendly rice production. Some local residents began to create wetlands as the storks returned. Others now manage once-fallow rice paddies as biotopes. We continue to be unsparing in these efforts to protect the environment and allow people and wild creatures to live in harmony.